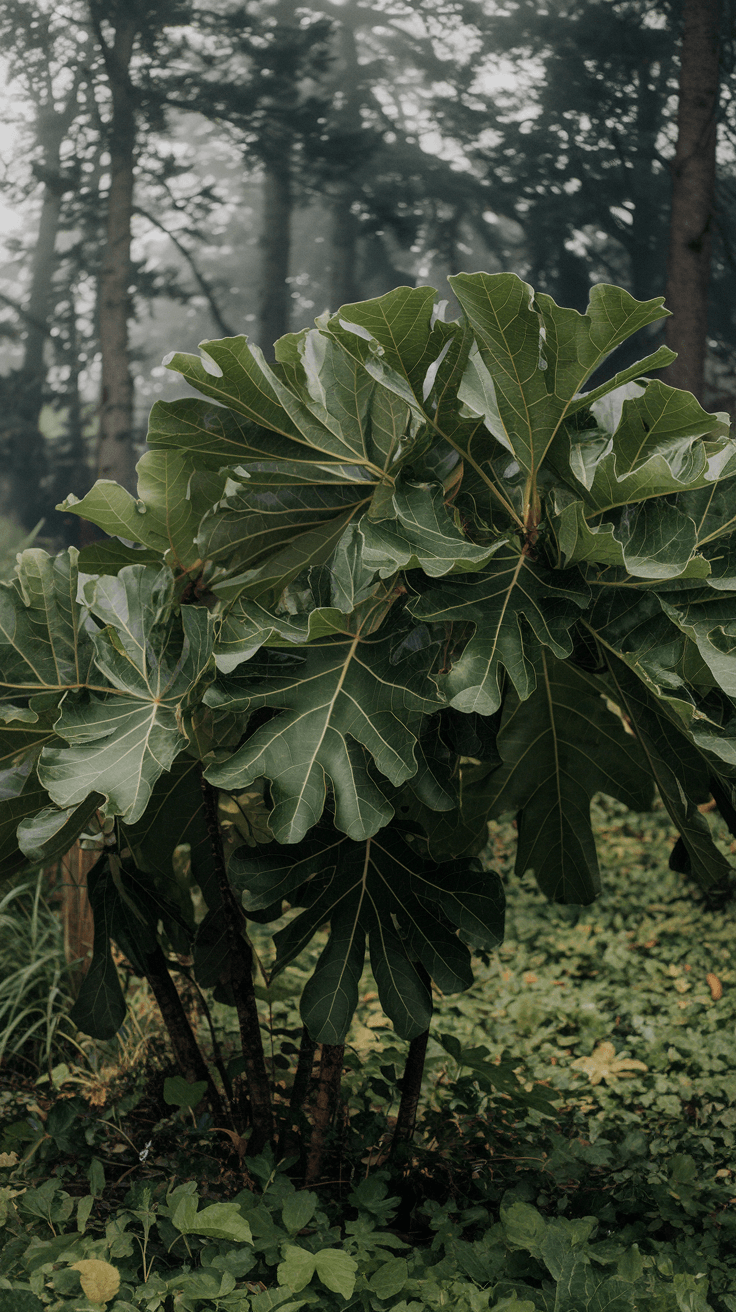

Picture your carefully positioned fiddle leaf fig in its decorative pot, standing elegantly in your living room corner. Now imagine that same species as a towering 50-foot giant in the dense West African rainforest, its massive trunk wrapped in vines and its roots competing with hundreds of other species for space and nutrients.

The disconnect between the manicured houseplant and its wild counterpart is staggering, yet understanding where fiddle leaf figs come from and how they actually live in nature transforms how you care for them at home.

I’ve spent years studying the relationship between houseplant care and natural habitat conditions, and the fiddle leaf fig represents one of the most dramatic examples of how wild origins dictate indoor needs.

The temperamental reputation these plants have earned stems largely from misunderstanding what they require—requirements that make perfect sense when you see how they’ve evolved to survive in their native environment.

This guide reveals the true natural habitat of Ficus lyrata, exploring the specific conditions they experience in the wild, how their growth patterns differ dramatically from potted specimens, and which lessons from their native range will immediately improve your success with these plants indoors.

The West African Rainforest Home

Fiddle leaf figs are native to the lowland tropical rainforests of western and central Africa, with their range extending from Cameroon west to Sierra Leone and south through parts of Angola.

These aren’t the dense, dark jungles of popular imagination but rather complex forest ecosystems with distinct layers—and fiddles occupy multiple levels depending on their life stage.

The climate in these regions is consistently warm and humid, with average temperatures ranging from 68-77°F year-round and humidity levels frequently exceeding 60-80%.

The rainfall pattern in their native habitat is crucial to understanding fiddle care. These regions experience distinct wet and dry seasons rather than constant precipitation. During the rainy season, which can last 6-8 months, intense downpours occur almost daily, saturating the forest.

But the soil drains quickly—the combination of sandy, porous substrates and sloped terrain means water never pools around roots for extended periods. The dry season brings significantly reduced rainfall but maintains humidity through morning dew and the moisture-retaining canopy.

What surprises many people is that wild fiddle leaf figs often begin life as epiphytes—plants that germinate in the crooks of other trees rather than starting in ground soil. Birds and other animals spread the seeds through their droppings, depositing them high in the canopy.

The seedling sends roots downward along the host tree’s trunk, eventually reaching the ground and establishing itself. This epiphytic beginning explains several care challenges fiddle owners face: these plants evolved to handle periods of limited water availability and need excellent drainage around their roots.

The light conditions in West African forests are intense but filtered. Even beneath the canopy, the tropical sun provides far more light intensity than most indoor environments.

Wild fiddles growing under the forest canopy receive what we’d call very bright indirect light—the equivalent of standing a few feet from an unobstructed south-facing window.

Those that establish in forest gaps or clearings can tolerate and even thrive in several hours of direct sun daily, their thick leaves providing protection against photodamage.

Pro tip: The fact that fiddles naturally experience strong seasonal changes in water availability explains why they tolerate slight underwatering better than overwatering—their root systems evolved to handle dry periods but never adapted to sitting in constantly wet soil.

Wild Growth Patterns and Characteristics

In their natural habitat, fiddle leaf figs are genuine trees, not the 6-8 foot potted specimens we maintain indoors. Mature individuals commonly reach 40-50 feet in height, with some specimens documented at over 60 feet.

Their trunks can exceed 18 inches in diameter, developing thick, furrowed bark that looks nothing like the smooth green stems of young houseplants.

This dramatic size difference reflects what the plant is genetically programmed to become when unrestricted by pot size and optimal conditions.

The growth habit in the wild is markedly different from indoor plants. Wild fiddles naturally shed their lower leaves as they mature, concentrating foliage in an upper canopy.

This isn’t the concerning leaf drop that worries indoor growers—it’s a deliberate strategy to invest energy in the highest, brightest leaves while abandoning shaded lower growth that contributes little photosynthesis.

A mature wild fiddle might have a completely bare trunk for the bottom 20-30 feet, with all foliage concentrated in a spreading crown at the top.

Branching patterns also differ dramatically. While we often prune indoor fiddles to encourage bushiness, wild specimens frequently develop as single-trunk trees in dense forest settings, branching extensively only once they reach the canopy layer where light is abundant.

In more open areas or following damage, they produce multiple stems from the base or develop branching lower down, creating the multi-stemmed appearance many owners prefer indoors.

The leaves themselves reach impressive sizes in optimal wild conditions.

While indoor fiddles typically produce 10-12 inch leaves at maturity, wild specimens generate leaves exceeding 18 inches in length. These massive leaves maximize light capture in the competitive rainforest environment.

The characteristic fiddle shape with its broad, wavy margins isn’t just aesthetically pleasing—it’s an adaptation that increases surface area while allowing rain to sheet off quickly, preventing fungal growth and physical damage from the weight of accumulated water.

Wild fiddles flower and fruit regularly, producing small fig-like fruits that attract birds and mammals. This reproductive success requires pollination by a specific species of fig wasp, which explains why indoor fiddles essentially never flower or fruit—the wasp doesn’t exist outside their native range.

The figs contain numerous tiny seeds that remain viable for only a short time, necessitating rapid dispersal and germination.

Expert insight: The bare lower trunks of wild fiddles teach us that bottom leaf drop isn’t always a crisis. If your mature fiddle is dropping lower leaves while actively producing new growth at the top, it may be following its natural pattern rather than experiencing a care problem.

Soil and Root System Adaptations

The soil in West African rainforests bears little resemblance to standard potting mix. It’s typically a loose, sandy loam rich in decomposing organic matter but exceptionally well-draining. Leaf litter, fallen branches, and the constant decomposition cycle create a nutrient-rich but airy substrate.

The rapid drainage combined with frequent rainfall means roots access abundant nutrients but never sit in waterlogged conditions—even during the wettest periods.

Fiddle leaf fig root systems in the wild are extensive and opportunistic. When starting as epiphytes, they send aerial roots down toward the ground, sometimes wrapping around the host tree.

Once established in soil, they develop both deep taproots for stability and water access, plus spreading lateral roots that compete for surface nutrients.

This dual strategy allows them to weather dry seasons by accessing deep moisture while capitalizing on nutrient availability near the surface.

The mycorrhizal relationships fiddles form with soil fungi in their native habitat are crucial but often overlooked. These beneficial fungi colonize the roots, extending the plant’s effective reach for water and nutrients while receiving carbohydrates in return.

Indoor potting mixes lack these fungal partners unless specifically inoculated, which partly explains why potted fiddles can struggle despite seemingly adequate care.

Root regeneration capacity in wild fiddles is remarkable. Physical damage from storms, animals, or competition triggers rapid new root production from any viable tissue. This resilience translates to indoor settings—fiddles can recover from significant root loss if conditions are appropriate, though the process is slow.

Understanding this natural resilience gives confidence when addressing root problems like rot, where aggressive pruning of damaged tissue is necessary.

Action step: Replicate wild soil conditions indoors by using chunky, well-draining mixes that combine standard potting soil with significant portions of bark, perlite, or pumice. The goal is a substrate that drains completely within minutes of watering, never remaining soggy.

Applying Wild Habitat Knowledge Indoors

The most important lesson from understanding wild fiddles is that they need bright light—much more than most indoor environments naturally provide. Placing your fiddle in “medium light” essentially starves it compared to its evolutionary expectations.

The single most impactful change most fiddle owners can make is relocating their plant to the brightest possible location, ideally within 3-5 feet of a south or west-facing window. This mimics the bright, filtered light of their natural understory habitat.

Water management should follow the wet-then-dry pattern of their native climate. Rather than maintaining constantly moist soil, water thoroughly when the top half of the pot has dried, then allow that dry-down to occur before watering again.

This replicates the cycle of heavy rain followed by drying periods that fiddles evolved with. The common advice to water on a schedule ignores that natural patterns are event-based, not time-based.

Temperature stability matters more than hitting a specific number. While fiddles tolerate a wide range (60-85°F), wild specimens experience remarkably consistent temperatures due to the moderating effect of dense forest.

Indoor fluctuations—blasting heat in winter, cold drafts from windows, or air conditioning directly on the plant—create stress that wild fiddles never encounter. Positioning away from vents and drafty areas provides the stability they’re adapted to.

Humidity requirements are real but often overstated. While wild fiddles experience 60-80% humidity, they’ve proven adaptable to lower levels indoors. The key is avoiding extremes—desert-dry air below 30% causes stress, but typical indoor humidity of 40-50% is acceptable if other conditions are optimal.

Focusing on light and watering yields better results than obsessing over humidity alone.

Conclusion: Bridging Wild Origins and Indoor Care

The dramatic difference between a 50-foot rainforest giant and your living room fiddle isn’t just scale—it’s a reminder that houseplants are wild organisms we’ve convinced to survive in artificial environments. Every quirk and requirement your fiddle displays traces back to adaptations developed over millennia in West African forests.

The need for bright light? It evolved competing for sun in dense jungle. The sensitivity to overwatering? Its roots developed in fast-draining forest soils and epiphytic beginnings. The tendency to drop lower leaves? That’s standard procedure for a tree investing in its highest, most productive foliage.

Understanding these connections transforms frustrating care challenges into logical responses to environmental mismatches. When your fiddle struggles, ask yourself: “How does this condition compare to a West African rainforest?”

The answer usually points directly to the solution—more light, better drainage, appropriate dry-down between watering, or greater consistency in temperature.

Your goal isn’t replicating a rainforest exactly but providing the essential elements—bright light, appropriate wet-dry cycles, warmth, and well-draining substrate—that allow this wild tree to thrive in captivity.